Also, check out the animation on worldmapper. It is an amimation that shows how the world map changes when moving from the number of people living of less than $1 per day to those living of $200 or more.

Read more!

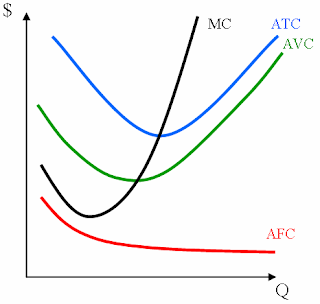

Banerjee and Duflo, in their paper, "The Economic Lives of the Poor" for which I wrote a small summary adress the problem of a lack of scale of microenterprises. This problem essentially means that many microenterprises operate at such a small scale, that they actually are not efficient. In microeconomic terms, efficiency is reached if average unit costs are minimized. If we have decreasing marginal cost (or constant marginal costs and fixed costs, which are spread of a larger number of units), this will imply decreasing average costs.In industrial economics, there exists then something which is called the "minimum efficient scale", which corresponds to scale where average unit costs are minimized. The minimum efficient scale will tell us, how many firms will operate in a long run equilibrium in a certain, perfectly competitive market at zero profits.

Now -- what does all this microeconomics have to do with microenterprises or microentrepreneurship? Banerjee and Duflo give the example of "dosa" makers in Indian cities.

Dosas are filled pancake like pastries, which constitute a typical breakfast in India. They write, that on any given morning, in urban slums women open some stalls on the streets and sell "dosas" to passerby's. Making and selling dosas essentially neither requires skills nor any capital equipment. So there is a situation where we literally have free entry.

Most of the time spend by women is to wait for passing by customers. Banerjee and Dulfo argue:

"Many of these businesses are probably operating at too small a

scale for efficiency. The women making dosas spend a lot of time waiting:

having fewer dosa-makers who do less waiting would be more efficient. In fact,

it might make sense in efficiency terms for the dosa-makers to wor in

pairs: one to make the dosas and one to wrap them and make change."

But why don't the women team up?

There must be a mechanism that prevents this from happening. Potentially, one mechanism is a behavioral one - lack of trust?

Or it may simply be, that as soon as somebody teams up with somebody else, another dosa maker opens their stall at the now vacated one, thus reducing the rate of arrival of new customers for all other dosa makers. So there may be something like a common pool problem, where all dosa makers essentially earn the average revenue. A common pool problem is for example the cause of overfishing, as essentially all fishers earn the same average revenue, each marginal fisher will actually reduce the average revenue of all other already existing fishers.

Here, each additional dosa maker reduces the rate of arrival of customers for all other dosa makers. So, when individuals do not team up, they essentially all earn the same average revenue. Now, if two individuals team up in an attempt to increase scale, actually, the average revenue for all others goes up, making it attractive for somebody else to open a stall for the now vacated one.

Now, however, the ones that teamed up need to split this revenue by two, which would render them worse off as before. So what they observe may something be like a self-enforcing bad equilibrium, that due to free entry maintains itself and makes it impossible for the dosa makers to actually reach the efficient region.

Maybe such a logic (I am of course not sure whether the argument is fully consistent, but it somewhat seems plausible), is the cause for a lack of growth of microenterprises in developing countries.

One striking observation: a typical household in Udaipur could thus spend up to 30% more on food by sacrificing the consumption on alcohol, tobacco and festivals. As undernutrition is strongly correlated with desease riddenness, spending more on food should seem like a good investment.

Consider now some general remarks of the paper considering the whole sample.

Spending patterns

This section investigates the consumption patterns that the poorest of the poor follow. One key observation across all countries is that they spend between 56 to 78% of the income is spend for calories.

There are however significant expenses not on calories but on "luxury items" such as alcohol and tobacco or festivals.

The share spent on food is about the same for the poor and the extremely poor, suggesting that the extremely poor do not feel an extra compulsion to purchase more calories. Deaton and Subramanian (1996) found that even for the poorest, a 1% increase on overall expenditure translates into about 2/3 of a percent increase in the total food expenditure of a poor family.

The authors also note that consumers do not purchase the goods with highest calorie count per $ spent, but they are more inclined to spend on better tasting calories.

This is a first puzzle: despite the finding of Deaton and Subramanian (1996) suggesting that the poorest people consume slightly less than 1400 calories per day, which is about 1000 calories short of the suggest daily diet, the poorest of the poor spend their income not on the foods that offer most "calorie value for money".

Health and well being

The paper mentions the example of Udaipur where most of the poor adults have a body mass index below the standard required levels, they also tend frequently feel sick or weak and report symptoms of disease caused by poor nutrition, such as anaemia.

Cutting meals however occurs every now and then. The authors argue that saving should be a way for the individuals to deal with healthcare emergencies and other emergencies, yet, savings is in general very low. This will be investigated further by the authors.

Investment in Education

Almost no money is spend on education - this seems to hold for rural as well as urban areas. However, a reason for this is, that that children in poor households typically attend public schools or other schools that do not charge a fee. However, due to widespread absenteeism, school attendance in public or private schools need not be a guarantee for actually acquiring human capital (see e.g. the Duflo, Hanna, Ryan (2007) paper, which describes the problem and presents the results of a field experiments in which teachers were given incentives to actually show up for work).

How do the poor earn their living?

Most income is earned from micro entrepreneurship requiring neither capital nor skills. The poor seem to follow multiple occupations. A large fraction of work time for rural poor is spend on agricultural work, however, th poor only cultivate the land they own, no more and not less.

The small parcels however, can not sustain them by themselves, which renders the most common occupation for the poor in Udaipur, is for example working as a daily labourer. So there is an apparent pattern of diversification among rural households, which may be rationalized by reducing the risks taken, by choosing multiple occupations. However, the authors present the case of non realized economies of scale arguing that many of those businesses are probably operating at too small a scale for efficiency.

The poor also use temporary migration, as in rural areas, most daily labourers would not be able to find a job. However, the migration spells are usually quite short.

The authors note the prevalence of a lack of specialization. Poor families do seek out economic opportunities, but they tend not to get too specialized. They do some agriculture, but not to the point where it would afford them a full living. They also work outside, but only in short bursts – they do not move permanently to their place of occupation.

Markets and the Economic Environment of the Poor

The economic choices of the poor are constrained by their market environment. The amount they save should vary with their access to a safe place to put their savings. Other constraints result from a lack of shared infrastructure.

The authors identify the lack or the underdeveloped nature of credit markets as a potential reason explaining the lack of specialization. The data suggests that very few of the poor households get loans from a formal lending source like a commercial bank or a cooperative; most of them get from informal sources like money lender, shopkeepers or even relatives and neighbours (from your social network).

Credit market failures and resulting high interest rates may be rationalized by severe problems of moral hazard or adverse selection (or they may be a signal of the high returns to capital in microenterprises). The authors argue that the high interest rates seem to occur not directly because of high rates of default, but as a result of the high costs of contract enforcement. While delay in repayment of informal loan is frequent, default is actually rare. Issues of moral hazard and problematic enforcement have been e.g. tackled by microfinance and group lending of the form advocated by the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh.

I am now jumping some aspects of the paper which I consider not so relevant at least for my interests. The paper asks several interesting questions that are developed in the course of the paper and it seeks to provide some or at least partial answers.

Understanding the Economic Lives of the Poor

The paper argues that many things about the lives of the poor start to make more sense once we recognize that they have very limited access to efficient markets and quality infrastructure. The poor, who typically own too little land relative to the amount of family labour and that are therefore the obvious people to buy more land, suffer from lack of access to credit. This gets reinforced by the difficulties that the poor face in getting any kind of insurance against the many risk that a farmer needs to deal with: so a second job outside agriculture secures him against much of that risk.

Questions that I think are particularly interesting is the role of the foregone economies of scale.

Papers referred to in post: